Why a public debate is required to define and implement “fairness” in insurance pricing

24 February, 2020 Chris Sandilands

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), one of Britain’s financial regulators, will soon be publishing its final report on pricing personal lines (retail) insurance. Coverage can be found on our blog with additional insight available to our Market Intelligence subscribers.

The interim report identified 6m customers it believes are paying excessive prices for their insurance. Of these, 2m are “vulnerable”. The final report will put forward remedies.

We are concerned that the FCA’s remedies are being made in the absence of public consensus about the role of insurance in society. Motor insurance is unique in that it is compulsory yet sold by commercial enterprises and priced based on the expected profile of the buyer.

This throws up three questions:

- Is risk rating appropriate?

- What is acceptable price discrimination?

- Are variable margins appropriate?

1. Is risk rating appropriate?

In most countries, motor and home insurance is priced according to an estimation of the risk profile of the insured plus a margin. The impact is that different customers pay different prices for the same product.

There are two reasons why risk premiums could vary (ignore margins for now): the actual claims experience and the assumed future claims experience of the customer.

It feels reasonable that the first of these – actual claims experience – should confer an advantage or disadvantage on a customer in order to encourage claim prevention. The no claims discount is a mechanism for this.

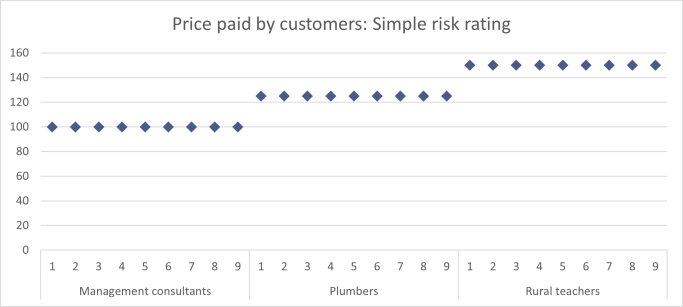

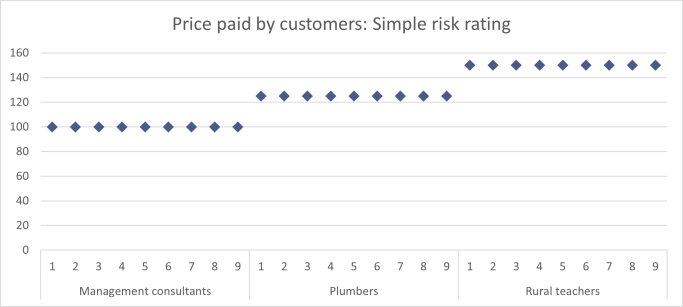

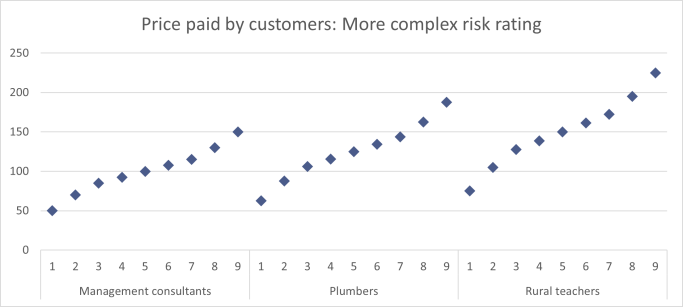

But should customers pay different prices based on their expected claims? Is it fair that young people are all assumed to be ‘worse risks’ and pay sky-high prices for motor insurance? Is it fair and desirable that rural teachers, who rely on their car to get to work and may have a higher claims experience as a group, pay more than an urban management consultants who use their car once a week to go shopping?

Instinctively it feels obvious that risk rating is good. After all, the fact that one group pays more than another is based on the observation that some groups have more claims than others.

But risk rating is not standard in all insurance markets. For example, some (admittedly less “sophisticated”) markets price on simple, standard market tariffs. UK annuities were, until relatively recently, not risk priced and instead relied on population-level mortality charts. The UK health ‘insurance’ system (NHS) is paid for out of taxation; there is no surcharge for smokers or builders who are more likely to end up in hospital. Health is a public good; why not critical mobility?

This is an issue which only public policy can solve. Ignoring potential brand benefits and other effects, were an insurer to bring down the cost of insurance for, say, young drivers unilaterally, it would be directly reducing profits as it would be unable to charge greater prices elsewhere. And anyway who has said that those other segments should be overpaying to subsidise the younger drivers?

In other words, if you want to level prices, you have to change the rules of the game.

2. What is acceptable price discrimination?

Let’s assume that risk rating is appropriate.

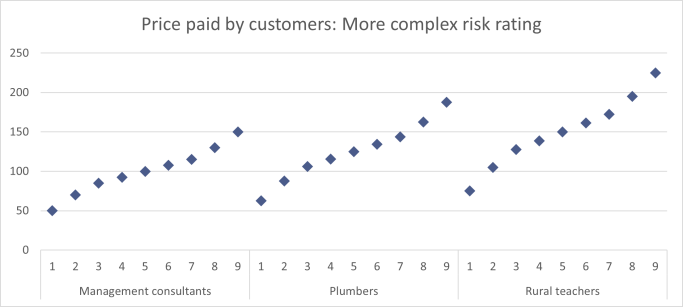

Ignoring margins again, any number of factors could influence the price of an insurance policy, from the address of the policyholder, to the car type, and the age of the driver.

But it cannot be anything. For example, long-established “redlining” laws prevent US insurers from using certain characteristics such as race in their pricing. In 2012 the EU introduced the Gender Directive which prevented insurers from using gender as a pricing factor.

But where is the line between an acceptable and unacceptable rating factor? Gender is not allowed but age and wealth are.

Things are only going to get more complicated. The advance of data and computational techniques will make pricing ever more granular. This will increase the skew in pricing, with the potential to put insurance out of reach for certain demographics. What will the young teacher in the Scottish Highlands, who has no option other than driving over icy accident hotspots twice a day for six months of the year do when her price increases?

Of course, some market solutions will emerge. Some insurers may specialise in young Scottish teachers by building a more granular understanding of their precise routes to work, or by nudging certain risk-reducing behaviours (for example through telematics). But these solutions are opportunistic, tactical propositions and only exist because the underlying market has these skews in the first place and because the problem is big enough to merit developing a solution at all.

So the public policy question is: if risk rating is acceptable, what factors are acceptable and which not? How close to “segment of one” do we want to get, or do we believe that some degree of risk pooling is in the public interest? Public policy has merely scratched the surface of this debate.

This is again a situation which the market is unlikely to be able to solve itself for the same reasons as above. Furthermore, any insurer reducing the skew by eliminating a rating factor is likely to over-index on those under-priced segments, thereby exacerbating their profit hit.

3. Are variable margins appropriate?

The first two points focused on risk pricing. In this section we consider margins – and in particular the “street pricing” process.

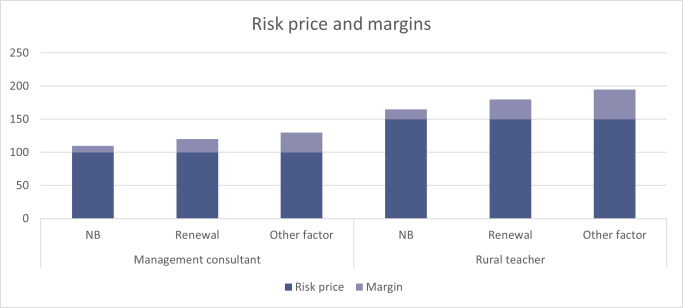

Best practice pricing says that insurers determine the fully loaded risk cost and then apply a margin which is broadly determined by a view of customer lifetime value and price sensitivity (“elasticity”).

This is the area into which the FCA has waded with its Pricing Fairness report. The regulator plans to ban excessive margins for vulnerable customers such as the elderly or mentally impaired.

Whilst few would disagree with the principle of not exploiting the vulnerable, the practicalities of implementation raise many questions.

First, and perhaps most obviously, what is the definition of “vulnerable”? Is an internet-savvy but time-constrained single mother in her 30s “vulnerable” for the purposes of insurance pricing? How you codify the line between a “vulnerable” customer and someone who does not switch due to laziness?

And what is the principle? Society does not seem to have a problem with last-minute holiday bookers paying a premium on flights and hotels, so why not disorganised insurance buyers? The broader the approach to protecting customers, the closer you get to a market tariff.

Second is the question of exploiting elasticities.

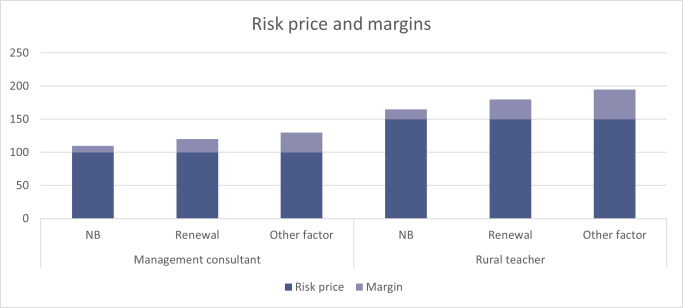

Consider the two customers above. As we noted in our analysis of the interim report, the FCA has decided that restrictions on price walking are necessary. That means that the two middle columns – where margin is increased on the basis that the customer is renewing – will not be permitted.

However, that is not to say that elasticities cannot be exploited. Let’s go back to our Scottish teacher. Perhaps few insurers are willing to provide cover, so those quoting can push their margin up (right column). Is that “fair”?

And margins are arguably not really the core issue in terms of consumer outcomes in this debate. Let’s imagine insurers apply a 10% profit margin to management consultants and a 5% margin to rural teachers: teachers would still be paying considerably more for their insurance.

So what is the answer?

The purpose of this article is not to propose an answer: that is an extremely complicated challenge which has so far occupied the FCA for 18 months and is generally acknowledged to have the potential to unleash any number of unintended consequences. We noted a line in the FCA interim report where it seemed to be backing away from long-term interventionist measures likely for this reason: “We will consider if there is a case to remove them should they successfully tackle harm and the market has developed sufficiently so that they are no longer required.” [1.15]

Instead the intention is to point out that the regulator cannot, in our view, determine a sustainable, “fair” approach to insurance pricing until some fundamental questions have been answered by society. Is mobility a public good and if so what mechanisms should there be to ensure broad access? Pricing Fairness only tackles a small slice of this question – the application of margins, but not at all the approach to risk sharing in society.

But closer to home, it is hard to see how a market can be both commercial and competitive and have interventionist controls on pricing. The FCA’s intervention will no doubt resolve some unwanted distortions but at best leave others and at worst create new ones.

We await the FCA’s solution with interest.